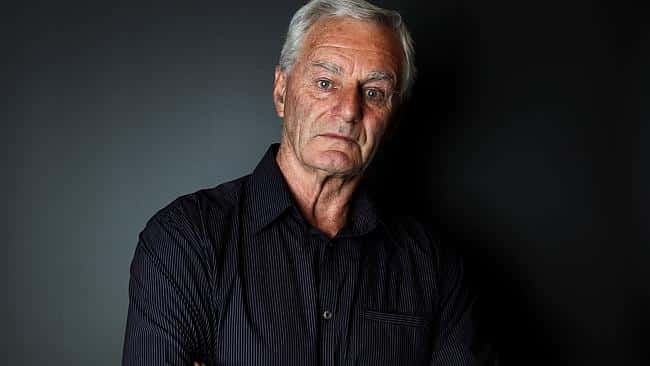

As the industry gears up for Medicinal Cannabis Awareness Week, former Northern Territory and federal police commissioner Mick Palmer urges governments not to repeat the mistakes of the past.

When I joined the Northern Territory Police, the offence of Ward Drink Liquor (WDL) was in force. The law focused solely on Indigenous Australians, and provided that Aboriginal persons whose names were not listed in a citizens register (a government gazette-style publication that listed all Aboriginal people who had been deemed or declared to be citizens) were classified as wards.

As wards they committed an offence of WDL for simply drinking alcohol, for which they were highly likely to be arrested and even imprisoned. The law was only repealed in 1967.

The intent of the law may have been to protect Indigenous Australians from the damage and dangers of alcoholism and to stop or deter them from drinking. But the reality was it did neither because it focused on the symptoms and did nothing to address the causes of the problem or the reasons for the behaviour.

Indigenous people still drank alcohol, the only difference was they were likely to be arrested, and often imprisoned, for doing so. Apart from being hugely discriminatory, the law punished the very people it was supposed to protect.

Such early operational experiences caused me to question the law and ask whether some of the behaviours addressed in our criminal codes should be crimes at all.

I remember being required to question a young man in his Darwin hospital bed who had attempted to take his own life. He had committed the then crime of attempted suicide.

Why anyone would want to arrest, charge and convict someone in his circumstances, even then, was almost impossible to understand.

The criminal justice system of the time, however, provided no avenues for support, protection, or treatment. The focus was solely on punishment, in the mistaken and simplistic belief that this would act as a deterrent to behaviour seen, at that time, as unacceptable.

Attempted suicide, thankfully, is no longer an offence in Australia.

But the lessons continued. The crime, then commonly known as buggery or sodomy, covering consensual sex between men, remained an offence in Australia until at least the late 1970s, with South Australia becoming the first Australian jurisdiction to fully decriminalise homosexual acts on August 27, 1975.

There are gay people living today, some of whom are dear friends of mine, who can still remember a time when the ‘abominable’ crime of buggery carried a sentence of 14 years’ imprisonment.

The death penalty for sodomy was only removed from the statute books in Victoria in 1949.

The reality is our history is littered with prohibitionist-type decisions which proved to be counter-productive, hugely discriminatory, bigoted, unfair, unnecessary and, in many cases, seriously harmful.

Governments must be prepared to heed the ‘bad laws’ lessons of the past if we are to achieve more positive and constructive outcomes in the future.

It would be difficult to identify a more deserving and obvious example of this than medicinal cannabis. Despite the advances that have been made, the restrictions still surrounding access could not be sustained on any objective assessment.

The medical evidence is overwhelming and I urge governments to heed the lessons of history, demonstrate genuine leadership, and take the opportunity to make a real and positive difference.

We all surely have an obligation to do everything we can to ensure we do not repeat the mistakes of the past.

Mick Palmer is an ambassador for the Australian Medicinal Cannabis Association (AMCA).